By Sarosh Bana, APSM Correspondent

By Sarosh Bana, APSM Correspondent

As the world determinedly grapples with the cataclysm of the coronavirus pandemic, India’s Narendra Modi government remains unwavering in its pursuit of establishing an authoritarian Hindu Rajya (Hindu State).

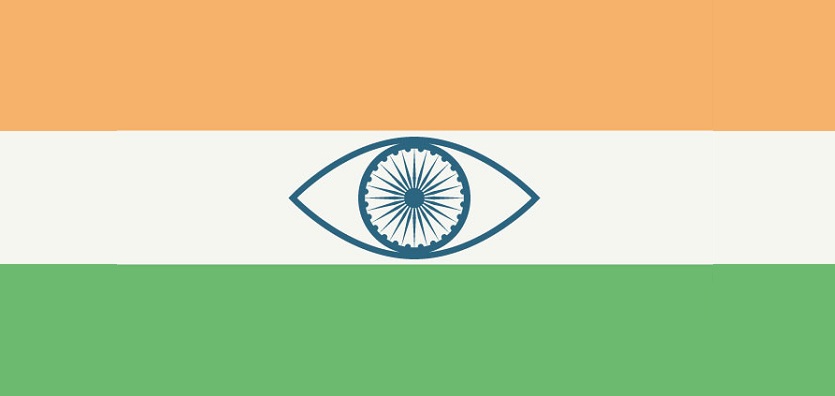

Stifling all dissent and opposition evidently lies at the core of this nationalist agenda, under which the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is creating a mass surveillance photo-identity database across the country that will be bolstered by the largest national automated facial-recognition system (AFRS), after China’s.

AFRS technology has been used by the police in the capital city of New Delhi and its neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh to identify those who had participated in protests that have raged since December against a new citizenship law widely perceived to discriminate against the Muslim community. Police film and take photographs of these protest rallies and feed the footage to the AFRS, which then transfers “identifiable faces” of the protesters to its dataset. These images and footage are subsequently manually screened to select and identify those deemed “habitual offenders”.

On the basis of these datasets, the police in Uttar Pradesh, where its BJP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath vowed “revenge” against the protesters, stormed into and ransacked the houses of the suspects and dragged them away to prison. Adityanath lauded the police action and authorised the auction of the raided properties as reparations for the damage caused by the protests. He also directed hoardings to be erected in public places sporting oversized photographs of the political activists together with their names, addresses and telephone numbers, rendering them and their families vulnerable to further attacks by the police and the armies of trolls and vigilantes sponsored by the political leadership. The posters were, however, pulled down on court orders.

The AFRS technology has been in use for some time now, as for instance to screen crowds at a political rally of Prime Minister Modi in New Delhi on 22 December 2019. The dataset was put to use for the first time at this event to weed out “miscreants who could raise slogans or banners” at the Prime Minister’s rally. Each attendee at the rally was reportedly captured on camera at the metal detector entry point and live feed from there was matched with the facial dataset within seconds at the control room set up at the venue.

Camera images have also been scanned against face images from footage of various protests in the capital. Such targeted surveillance has caused widespread disquiet, with many feeling threatened by what they consider an abuse of state power that contravenes the fundamental right to privacy enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

People have been particularly alarmed by the police excesses, with the police smashing closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras in the streets and on university and college campuses before rampaging against the agitators, most of whom were students, both boys and girls. Numberless videos of police brutality nonetheless emerged on social media where security personnel could be clearly seen masking their faces as they fired at and baton-charged unarmed protesters and even students in their hostels and libraries.

Police protocol mandates sounding warnings to agitators as the first step in riot control, followed only later by caning at the leg level. In the present police action that brazenly violated human rights, activists were from the initial stage viciously thrashed on their heads, at times by mobs of policemen against one individual. At least five school-children detained during the protests were tortured in police custody. The government declined investigation into the police action, asking complainants to move the courts if they felt aggrieved. The courts have put off the hearings, while the police maintain they acted in self-defence, despite the widely available video evidence to the contrary.

The AFRS technology used by the police was of Innefu Labs, a New Delhi-based startup that provides Information Security and Data Analytics solutions. Its facial biometrics software enables gait and body analysis as well, with police in about 10 other Indian states also deploying Innefu products. There are few companies like Innefu Labs in India that have the capability of deploying Artificial Intelligence (AI) for facial biometrics. Some of their foreign peers present in India include Japanese tech major NEC Corporation’s subsidiary, NEC Technologies India, which has supplied biometrics to four airports in the country. A TechSci Research report estimates India’s mass surveillance market to grow from about $700 million in 2018 to over $4 billion by 2024.

India is currently leagues behind China in the public surveillance sphere. A Comparitech survey of 120 cities worldwide lists eight Chinese cities among the top 10 most-surveilled cities in the world. Chongqing, a major Yangtze River port city in southwest China, tops the charts with 2.58 million cameras for its 15.35 million population, that is, 168.03 cameras per 1,000 people, while New Delhi, which is ranked 20th in the listing, has 179,000 cameras for its population of 18.6 million, calculating 9.62 cameras per 1,000 people.

Reporting that the digital age has facilitated live video surveillance the world over, Comparitech notes that CCTV monitoring can be used for crime detection and prevention to traffic supervision as also for monitoring industrial and commercial spaces. Live video streams can now be remotely accessed or stored on the internet, while face recognition technologies are enabling the scrutiny of all coming within their range.

India’s National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has been tasked with implementing what would be one of the world’s biggest biometric projects. Last July, the Bureau issued a global request for proposal (RPF) for the project to create a nationwide grid of facial recognition system, requiring the bids to be submitted within a month. Eighty representatives of prospective bidders attended the pre-bid meeting at the NCRB.

The RPF, however, met with little success, as it was riddled with delays owing to its lack of clarity on several issues and the possibility of its being incompatible with prevalent legislation. The deadline has subsequently been extended six times and has now been set for the end of March, but will likely be extended again on account of the coronavirus incidence.

Experts feel the NCRB’s bid document lacks clarity as it does not specify how the personal data gleaned will be shared with police stations across the country, how precise it will be, how this information will be safeguarded, which officials and agencies will be empowered to access it, and for how long and for what specific purpose can they retain it.

There is besides the question of ethics behind collating such data surreptitiously, as the subjects of this database will have no knowledge or control over how their images will be used. Moreover, if such an expansive database gets compromised, it can have a countrywide impact. Cybercriminals are well aware of the AFRS technology and the level of cybersecurity in India, and will not find it difficult to trick or hack into a facial-recognition system.

The NCRB has declared that the underlying purpose of the proposed facial recognition system will be to track criminals and find missing children. But most realise what its primary objective will actually be – to identify dissenters and those deemed inconvenient by the current dispensation.

Only recently, considerable alarm was generated by a rabid mode of cybersnooping on select citizens by an Israeli firm presumably engaged by the Indian government. The 18 citizens so targeted included civic and human rights activists in prison on charges of sedition, as also lawyers fighting their cases and academics who spoke up for them. They were targeted by Pegasus, a state-of-the-art mobile phone spyware suite produced by Israel’s NSO Technologies Group, and the intrusion was through the video calling feature of the popular Facebook-owned WhatsApp messaging platform.

Many saw the BJP government’s hand in this, since NSO caters only to governments and not private agencies or individuals, and that too after clearance from the Israeli defence ministry. It was felt that if the authorities had access to the phones and computers of the imprisoned civic activists and their lawyers, they may well have also planted evidence, especially because the government has hitherto been able to only furnish digital “evidence” from their electronic devices to keep them in jail.

Since coming to power in 2014, the BJP-led government has been striving to bring India’s entire population under surveillance. In 2016 it introduced the personal data gathering medium called aadhaar that has by now enrolled around 93 per cent of India’s overall population of 1.34 billion, making aadhaar the world’s largest biometric database.

While this national identification platform was originally conceived as a means to provide efficient access to government welfare schemes meant largely for the underprivileged, the BJP government made it mandatory for accessing a host of services like opening and operating bank accounts, filing Income Tax returns, and for applying for cellphone services, passports, driving licences, house subsidy, school admissions, death certificates, train tickets, and even for supplementary meals at crèches and maternity benefits.

In its statutory order of December 2018, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) designated 10 agencies to carry out interception of information “when required in national interest”. The notification evoked the Information and Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008, as well as the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, which permitted the interception, monitoring or decryption of any information generated, transmitted, received or stored in any computer resource. The government held that right to privacy could not override the need for gathering information for the cause of national interest and security.

This was the first time any Indian government had conferred such overwhelming scanning powers on its agencies. This move has been challenged in court, where the petitioners contended that while national security was indeed critical and paramount to any society, one should be circumspect about the government’s keenness to attribute its invasive surveillance practices to the cause of national security.

The government argued, “Grave threats to the country from terrorism, radicalisation, cross-border terrorism, cybercrime, organised crime, drug cartels cannot be understated or ignored and a strong and robust mechanism for timely and speedy collection of actionable intelligence, including signal intelligence, is imperative to counter threats to national security.” But the petitioners countered that if terrorists were to be monitored, it did not stand to reason that the average citizen should be too.

There were adequate means available to the government to safeguard national security rather than by bringing the entire population under pervasive surveillance. They noted, “The government has thus sought to establish a system of deep surveillance that is not in public interest and is fraught with a high risk of misuse and abuse.”