February 3, 2021

BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 1,914, February 3, 2021: Published with permission courtesy of the BESA Centre.

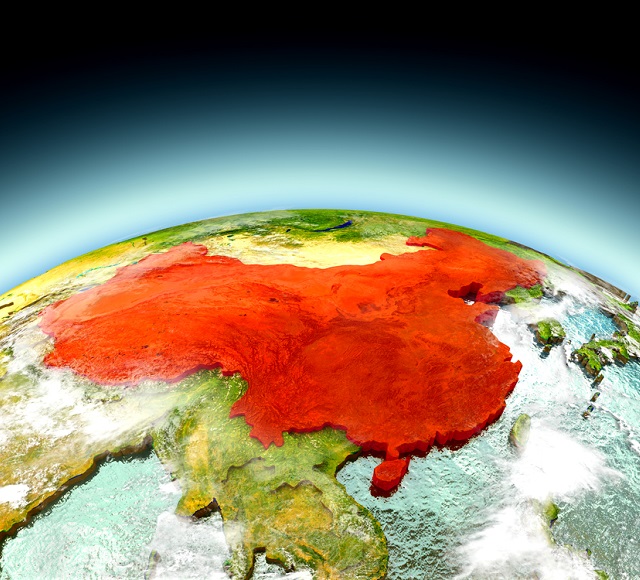

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: During his term as US president, Donald Trump employed an economic and foreign policy that challenged globalization in an attempt to stem the rise of China—but that did not prevent Beijing from taking its own steps toward multilateralism, free trade, and economic liberalization. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Sino-European Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) are indicative of this. President Biden will govern in a world in which Cold War frameworks do not apply. When looking for partnerships with allies to restrain China’s influence, he will encounter Beijing’s deep engagement in a globalized international environment.

Rising Sino-American antagonism and Washington’s emphasis on restraining Beijing’s influence remind some scholars of the Cold War period. Historian Niall Ferguson, for example, has written that a new Cold War has begun. Such comparisons are tempting, but China—unlike the Cold War-era Soviet Union—is well placed in the globalized international environment and developing quickly. While some 21st-century Western analysts have indulged in the wishful thinking that China would emulate the American model, Beijing has gone its own way.

Donald Trump reshaped the American political and economic approach to China. He put limits on the harmonious evolution of the bilateral relationship and inaugurated a new era in which hurdles were placed in the path of China’s economic drive forward. In July 2020, then Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivered a speech entitled “Communist China and the Free World’s Future.” As the title suggests, China’s governance model was perceived by Pompeo as antithetical to US and Western ideals.

Trump found it far from easy to persuade other countries to support this cause for two main reasons. First, his own administration introduced a new type of foreign and economic policy that was grounded in bilateral rather than multilateral cooperation and that challenged previous norms. The 2017 withdrawal of the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was a characteristic example that alienated US allies in the Asia-Pacific who had hoped in vain for American leadership. And second, some US partners in Asia and in Europe did not view China in Cold War terms but as a valuable partner. They strove to satisfy some American demands, but only to the extent that that could be done in a manner that did not frustrate Beijing.

In the interim, China has been concentrating on managing the ”unprecedented difficulties” in Sino-American relations that arose over the past four years without abandoning multilateral initiatives that promote globalization and liberalization. In the last months of 2020, those efforts yielded results.

In mid-November, China was among the signatories of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). RCEP will give the 10 ASEAN members and five additional countries (Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea) the opportunity to enjoy free trade and deliver benefits to their exporters, service suppliers, and investors through a single set of rules. Beijing’s role in the shaping of a new Asian supply chain in the post-COVID-19 era will be critical, as it constitutes the largest or second-largest market for all countries in the region and a key import supplier. A Peterson Institute for International Economics study anticipates benefits for China, Japan, and South Korea and losses for the US and India.

Additionally, on December 30, China and the EU concluded (in principle) negotiations for a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). CAI creates a new inclusive framework for Chinese investment in Europe and European investment in China. Unlike RCEP, it does not cover free trade.

From the Chinese perspective, CAI will further enhance Sino-European economic ties and perhaps facilitate its effort to unleash innovation domestically. From the European perspective, the deal will provide more access for EU companies to the Chinese market and rebalance the bilateral partnership.

Brussels believes its push for reciprocity was vindicated by CAI, but Trump’s Washington did not see it that way. Former Deputy National Security adviser Matt Pottinger blasted CAI and raised human rights concerns. For his part, Joe Biden’s nominee for National Security Adviser, Jake Sullivan, tweeted before the conclusion of the CAI talks that the new administration would welcome early consultations with its European partners on common concerns about China’s economic practices.

Sino-American competition is not only playing out in the US field. China is both powerful and patient and systematically endeavors to preserve, if not forge, a new world order that will guarantee its safe development. Negotiations for RCEP and CAI started in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Future objectives of President Xi Jinping include the signing of a free trade area among China, Japan, and South Korea and the realization of a free trade area in the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). Beijing will also look favorably on joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). CPTPP—the new version of TPP, which was signed by 11 countries but that excludes the US—was signed in 2018. Joe Biden has said he does not support rejoining the TPP but may try to renegotiate it to include stronger labor and environmental provisions.

Seeking for American leadership, Biden will find a different Asia and a different world. As he attempts to establish his own foreign and economic policy, he will have to contend with China’s deep engagement in a globalized international environment.