Confucius Institutes in the MENA Region

Re-published with permission from the BESA Centre.

Soft power is a crucial element in China’s strategy to achieve great power status.

Culture is one of the most visible elements of China’s soft power projection, a strategy encouraged by former President Hu Jintao in a 2005 speech in which he cited “soft power” as he stressed the need to promote Chinese culture.

This was reinforced by President Xi Jinping, who said in a speech, “We should increase China’s soft power, give a good Chinese narrative, and better communicate China’s message to the world.”

There are two schools of thought regarding Chinese soft power. According to the first, Chinese influence is rooted in its culture.

The soft power of any nation comprises ideas, beliefs, and ideals but also institutions and policies that exist within the framework of the nation’s culture.

The second school of thought states that soft power is the combination of a nation’s international image as reflected through national growth, strategic relations, and the absence of coercion.

Scholars also stress peace and security as characteristics of Chinese political culture and a fundamental tenet of Chinese foreign policy.

They claim that modern concepts of soft power have been part of Chinese strategic thinking since ancient times and are evident in present-day Chinese strategic thinking as promoted by President Xi.

China’s rich history and culture contribute to a positive image that enhances Beijing’s influence.

The showcasing of China’s culture and traditions has thus become an essential part of its soft power projection strategy.

One of the focal points of this strategy has been political and financial support for major global cultural enterprises, the most prominent of which is the establishment of Confucius Institutes (CIs) around the world.

Confucius Institutes

As of 2004, China has invested extensive resources and effort in establishing culture and language centers known as Confucius Institutes, named after the 6th century BC Chinese philosopher.

These institutes now represent one of China’s most significant soft power investments. China works to promote its Putonghua language (Mandarin is spoken on the mainland) and cultural traditions abroad, and CIs take the lead in this effort.

They offer Chinese language courses to university students, high school students, and businesspeople; host China-related conferences, lectures, exhibitions, film screenings, and other cultural events; and offer scholarships and academic exchanges.

China has invested extensive resources in establishing CIs worldwide. They operate within global universities and are managed by Hanban, the Office of the Chinese Language Council International, a branch of the Chinese Ministry of Education.

Hanban typically funds a CI’s establishment and provides teachers, while the local university offers infrastructure and network access. Since 2004, Hanban has set up 500 CIs around the world.

Officially, CIs promote the Chinese language and cultural activities among students and researchers.

However, they serve another purpose that is essential to CCP interests. Politburo member Li Changchun has described them as “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda setup.”

Most, if not all, Chinese entities that engage with their peers abroad unswervingly serve CCP goals by following official or unofficial guidelines and avoiding taking positions that might violate those guidelines or jeopardize the regime.

No matter how independent, persuasive, or flattering Chinese entities may seem, they all row in the same direction.

Therefore, although CI activities seem innocuous and cultural-academic in orientation, the PRC government’s control over their staffing and curriculum ensures that they will subtly promote CCP positions on issues like territorial disputes or religious minorities in China.

In most cases, CIs operate within universities as a collaborative initiative between a Chinese university and a local one.

This unique method of operation is the main distinguishing factor between CIs and cultural institutes operated by other countries (e.g., Alliance Française or Germany’s Goethe Institute).

The fact that CIs situated on foreign university campuses blur the distinction between the local university’s purview and China’s appears to be a strategic PRC effort to penetrate foreign campuses.

The Chinese government chose to place CIs at the heart of university education abroad, thereby building soft power centers that can influence foreign academic establishments.

In July 2020, Hanban, the Chinese government agency that launched CIs, renamed itself the Ministry of Education Center for Language Education and Cooperation (CLEC) as part of a rebranding exercise designed to counter negative perceptions.

Hanban spun off a separate organization, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), which now funds and oversees Confucius Institutes. CIEF is under the supervision of the Chinese Ministry of Education and is supported by the Chinese government.

The lack of transparency in CI financial transactions with their host universities, dissemination of propaganda, and on-campus censorship of CCP-sensitive discussions have spurred the closure of CIs around the globe.

The presence of CIs in the heart of academic campuses, combined with the economic, legal, and political pressure they are able to exert, restricts academic freedom and leads students, lecturers, and researchers to censor themselves.

More extreme allegations hint that CIs are forward positions that serve Chinese interests by collecting information and engaging in industrial espionage under cover of Chinese language courses, cultural events, and academic research.

In recent years, 113 universities, school boards, and governments in Europe, Canada, and the US have closed CIs down, though many have since reappeared in other forms.

While there have not yet been any closures in Asia, the trend is turning against CIs in some parts of the region.

Closures have not occurred in South America, Africa, or the Middle East and new CIs are opening in some of these areas, including South Africa.

The latest available official data say there were 541 CIs in 162 countries and regions as of the end of 2019.

That year, the number of CIs decreased for the first time since the program’s inception in Korea in 2004.

As of 2023, at least 129 universities, two governments, and three school boards in 11 countries will have cut ties with CIs.

These actions have resulted in at least 128 closures of CIs (some were co-hosted by more than one university).

Still, the global presence of CIs remains impressive, especially compared to longer-established language and culture promotion bodies.

It should be noted that Beijing planned to operate 1,000 institutes by 2020, but this goal has not been met.

Reverse Trend in Confucius Institutes in the MENA Region

By contrast, CIs have expanded their presence in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

In 2006, the first regional CI was founded at Beirut’s Saint Joseph University.

Since then, the number of institutes in the MENA region has increased and none has been closed down.

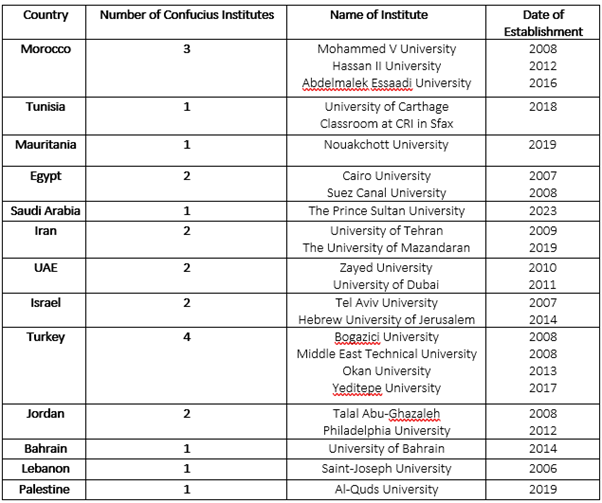

As of the end of June 2023, 23 institutes had been established in various countries, including Egypt (two), the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Morocco (three), Turkey (four), Tunisia, Mauritania, the Palestinian Authority, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Confucius Institutes in the MENA Region

Source: “Confucius Institutes Around the World 2023,” Dig Mandarin, January 7, 2023

One explanation for the opening of new CIs in MENA countries is that opinions towards China are mainly positive in the region, as demonstrated by recent Pew Research Center surveys.

In 2019, most people in the region held favorable views of China, while unfavorable views dominated the US, Canada, most of Europe, and most of the Asia Pacific.

The positive views evident in the MENA region stem from high levels of Chinese investment, trade, and development funding; the availability of Chinese goods at affordable prices; scholarships for study in China; and the provision of vaccines and other medical supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the perception of China as a counter to the US.

CIs have also been welcomed as they satisfy a demand for Chinese language education and improve the quality of education in the region.

Chinese tensions with Western countries mean there will likely be further closures of CIs in those regions, though they are unlikely to disappear completely.

Their future appears to be in the MENA region, South America, and Africa.

China has become a significant player in the MENA region. Its interests extend beyond traditional energy sources and encompass economic, geopolitical, and strategic considerations.

China has signed strategic partnerships and memoranda of understanding for economic activities with most MENA countries.

It has also established closer relationships with various regional organizations, including the China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), the Union of the Arab Maghreb (UAM), and the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF).

Finally, China has advanced its soft power projection in the region with humanitarian initiatives (medical aid during the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism, cultural centers, festivals, and workshops).

These initiatives are an attempt to secure a positive image in the region and encourage a view of China as a responsible power and trustworthy partner.

China’s role in the MENA region has grown in all aspects, including economic and diplomatic relations and on the military and strategic fronts.

A significant element of this relationship is soft power diplomacy, which has proven to be a catalyst for a burgeoning economic and political engagement.

China is pursuing soft power diplomacy to strengthen regional bilateral ties by highlighting religious, cultural, linguistic, and culinary aspects of its relationships.

As a tool of soft power projection, CIs have effectively penetrated the MENA region and have been welcomed.

They are crucial to promoting China’s positive image but are just one means of influence in the CCP’s toolbox.