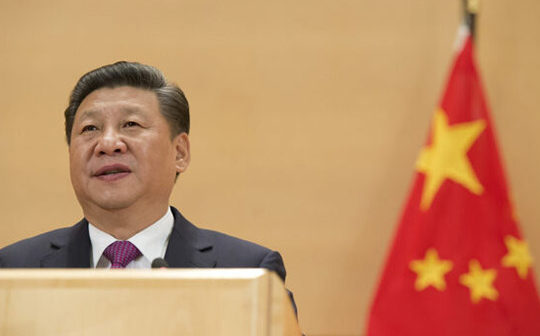

Xi Jinping, photo by Jean-Marc Ferré for UN Geneva via Flickr CC

BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 2,076, June 20, 2021 – Republished with permission, courtesy of the BESA Centre.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The announced withdrawal of the US from Afghanistan could represent an opportunity for Beijing to expand its geopolitical influence westward. This would be fraught with security risks for Xinjiang and Central Asia. Beijing might be creative in how it manages the Afghan problem, possibly establishing a quartet of states that share not only security and economic interests but a deep revulsion toward an America-led world order.

The US withdrawal from Afghanistan will create a geopolitical vacuum—the inevitable result of any withdrawal, be it physical or political. Another truism is that geopolitical vacuums, like all vacuums, never remain unfilled for long.

A key actor with regard to the Afghanistan question is China. To Beijing, Afghanistan is both a geographic corridor and a fertile ground from which security threats could emerge that threaten not only China’s hold over its restive Xinjiang province, but also its position in Central Asia—an area critical to the implementation of Xi Jinping’s signature policy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China’s interests in Afghanistan, with which it shares an 80 km border, have grown complex over the past decade. The US withdrawal plans stoked both short- and long-term fears in China. First is the security issue. Afghanistan hosted alleged Uyghur extremist organizations that seek an independent Xinjiang, groups that have been blamed by Beijing for terrorist attacks that occurred in China in the 1990s-2000s. Perhaps this was behind the allegation made by the Chinese leadership that the US withdrawal plans had “led to a succession of explosive attacks throughout the country, worsening the security situation and threatening peace and stability as well as people’s lives and safety.” Indeed, on May 8, 2021, a bomb attack outside a school in Kabul killed at least 68 people and injured more than 160. Similar sentiments were shared in a recent phone call between the Chinese and Pakistani FMs.

China also fears that from a decades-long perspective, the American withdrawal from the Middle East and Afghanistan might prove beneficial to Washington as it will serve two important goals for America. First, the vacuum will distract China from other regions (most notably the Pacific); and second, the US will have a freer hand and more resources available to focus on containing China in the South and East China Seas.

China is the key player here. No other power is sufficiently influential, either financially or geopolitically, to have an impact in the wake of the American departure on the entire territory from Central Asia to the Mediterranean. China has made tremendous progress in fortifying its position in this area, but it should be remembered that Beijing fears it was pushed down this road by the strength of the US and its allies in the Pacific. Indeed, it was concern about potential blowback from America on the seas in the event of conflict that caused China to look inward, to the heart of Eurasia, to offset its naval insecurities. Thence BRI emerged.

And there was space for China to fill. Central Asia, though a traditional space for Russian geopolitical influence, was fertile ground for Chinese economic activity. The same was true for Pakistan and, more recently, Iran. Further west, Beijing’s influence has been on the rise in the Mediterranean as well.

This took place at a time when America’s unipolar aspirations had been dashed, and the invasion of Iraq and military presence in Afghanistan had undermined US authority and that of the liberal internationalism project. In the long run, this caused pushback from regional states, and there are now increasingly concerted efforts to sideline Washington altogether in both peace talks and security matters. The circumstances were propitious for China to look westward, but US pressure was instrumental in setting off the process.

The US withdrawal presents China with a striking opportunity: the promotion of an alternative world order in which the Western military presence in Asia is reduced and China has greater room for maneuver west of its borders.

This also fits the vision of other like-minded states that now are forming an illiberal movement in which the Westphalian concept of primacy and inviolability of the state and its borders is feverishly upheld. This sentiment was echoed in the initial reaction to the US announcement by China’s FM Wang Yi, who argued that Beijing supports the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan and is ready to help promote future “stability and development.” In Beijing’s view, the US presence in Afghanistan deviated long ago from its original goal of combating terrorism and turned into a geopolitical project for preventing the growth of China’s power.

Still, in the longer term, a larger involvement by China in the Afghan conundrum would distract it from other critical geopolitical theaters where it competes with US. Thus, for China, the negative effects of the US withdrawal far outweigh the potential advantages it could bring to the Westphalian notion and general increase of Chinese power in West Asia.

What could then be a viable foreign policy option for Beijing to maintain a less harmful environment in Afghanistan? One idea propounded by analysts has been to argue that Beijing could look into transforming its fledgling and limited security presence in the north of Afghanistan into a wider military operation; i.e., a peacekeeping mission. This would depend on the level of non-state security threats, but the most likely security path Beijing would take is to merge efforts with other regional states to contain and, where necessary, wipe out terrorist and extremist cells in Afghanistan. Russia, Pakistan, and Iran would gladly work with China on this, as it would sideline the collective West and the US in particular in the region.

In a way, this motivation could bring forth a greater effort from the four participating states, as all the actors in the presumed quartet experience similar pressure (of varying degrees) from the West. They seek to establish, if not an entirely alternative world order (as in the case of China), at least a world order that is significantly remolded to suit their national interests. The quartet might even prove more effective than the Americans’ prolonged and unsuccessful state-building process in Afghanistan. Chinese analysts have already opined that cooperation between the regional states would provide a more effective security umbrella.

The quartet could foreswear efforts to ban the Taliban from governing the country but work on containing it where necessary, remaking and influencing the Taliban’s behavior so it fits the security objectives of China, Russia, Pakistan, and Iran.

Disinterest in countries’ internal governing systems is a hallmark of China’s world vision, according to which economic and security cooperation is the primary driver rather than liberal proselytism (or any other kind), as was unsuccessfully pursued by the US. This could be solid ground for cooperation with whatever government will be in power in Afghanistan.

Opting for a unilateral or even a quartet-led military solution to the Afghan problem would likely prove just as ineffective for China and the other three parties as it was for America.

Another novelty China could push for is allowing the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to take a more active security role in Afghanistan. This would serve as a model for similar future activities by the SCO, which has not yet had an opportunity to prove its mettle.

A more nuanced strategy would be sought—one that would make the Taliban cooperate, but more along the lines of China’s and the other potential quartet powers’ economic and security interests. It is unlikely that China will simply leave Afghanistan to its own devices. Though by the end of 2017 Beijing had scant investments in Afghanistan ($400 million), the country’s economic lure is too important to ignore—its mineral riches are valued at $1-3 trillion.

After US forces leave Afghanistan, China will face the problem of potential security blowback in Central Asia and Xinjiang. But it will also see long-term benefits in a region freed from the US military presence and the potential to set up an alternative mechanism for solving the Afghanistan problem.

China has close, near-strategic ties with Russia, Pakistan, and Iran, and might create a quartet to deal with the issue. It might seek more fundamental cooperation with the Taliban, but, as argued above, only within the framework of economic and security patterns benefiting the quartet and China in particular. Pakistan would oppose India’s participation, another power with an interest in the region, so China and the quartet would ensure that Delhi is excluded.

Eventually, and much to Western surprise, the system might work. At the very least, it will denigrate the role the West has played in Afghanistan and add another bloc to the alternative world vision championed by illiberal states.

Emil Avdaliani teaches history and international relations at Tbilisi State University and Ilia State University. He has worked for various international consulting companies and currently publishes articles on military and political developments across the former Soviet space.