By James MacHaffie

Introduction

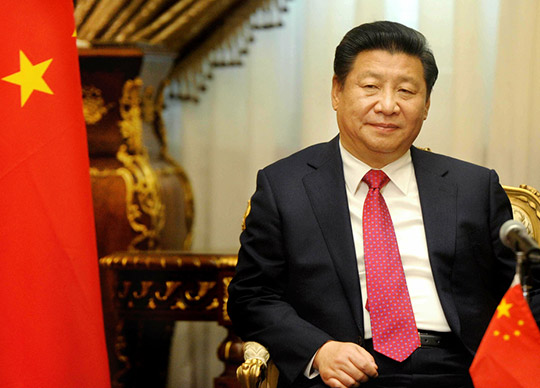

China’s cyber security strategy, first enounced in 2016, has evolved under Xi Jinping. It has become multilayered, with both civilian and military components that interact with each other. This military-civilian fusion (MCF) (junmin ronghe,军民融合) is integral to China’s cyber superpower ambitions. (China Brief, 2019) The ultimate goal is for China to become a “cyber superpower” (Wan luo qiang guo, 网络强国).

Xi Jinping delineated this goal in a speech on April 19, 2016. (“Speech at the Work Conference for Cybersecurity and Informatization,” Zai wan luo an quan he xin xi hua gong zuo zuo tan hui shang de jiang hua, 在网络安全和信息化工作座谈会上的讲话) (Xinhua, April 19, 2016) Both Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) see the control of cyberspace as critical for the long-term survival of the regime.

The first civil-military cybersecurity innovation center was unveiled in late 2017. (People’s Daily, December 28, 2017) In China’s peaceful rise to great power status the CCP has sought to project the image of strength, uniformity, and internal stability. (Xinhua, January 24, 2020) To that end, Xi has spearheaded efforts to restrict Internet access, and make China more resilient in the cybersphere, with the ultimate goal of having cyber sovereignty. In other words, to stifle dissent and exclude Western states as much as can be enabled.

MCF’s Two-Pronged Strategy

Beijing has denoted what amounts to a two-pronged strategy on cybersecurity with MCF, utilizing both military and civilian sectors, which overlap. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has taken the lead in Xi’s cyber strategy, recognizing the important role cyberspace plays in “informatized warfare.” (Xin xi hua zhan zheng, 信息化战争) (Xinhua, September 24, 2019). In the most recent Defense White Paper (Xinhua, July 24, 2019), the PLA recognizes cyberspace as a “security threat” to China (Yan jun an quan wei, 严峻安全威). As such, the Chinese military, working in conjunction with the civilian sector, especially the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) has made enhancing its role in cybersphere activity, looking for threats, a priority. (PLA Daily, September 14, 2020) The PLA’s role in domestic surveillance is slight, as its focus is on foreign (mainly US) influences on China’s cybersphere, with the Strategic Support Force being the lead agency in cyber warfare and security issues. (China Brief, 2016) However, recipients of foreign communications, if deigned harmful to the regime from a national security perspective, may be monitored, and punished under the national security laws. (SCMP, April 28, 2020) The main onus on implementing and overseeing the cybersecurity laws will fall on the CAC. The Cyberspace Administration was founded in 2014, tasked with ultimately implementing Xi’s cybersecurity policy. (Qiushi, September 16, 2018) The CAC decides which websites will be censored, and what content will be filtered through its firewalls.

While the coordination between the CAC and PLA Strategic Support Forces is loose, they still represent the two governmental organs that are responsible for implementing Beijing’s cyber strategy. The intersection of military and civilian control of Chinese cyberspace is consistent with Xi’s centralizing of power within the CCP bureaucracy itself, with centralized control of China’s cybersphere the ultimate goal. (PLA Daily, March 15, 2018)

Xi and the CCP, for the last several years, have incrementally been attempting to centralize control over China’s cybersphere. Beijing continues to establish innovation centers around the country to not only showcase and upgrade China’s technological innovations, but also to establish a link to MCF. (Xinhua, January 20, 2021) The point of these centers is twofold. One reason is to make the Chinese public more comfortable with the MCF notion, as the party-state realizes its goal to become a cyber superpower, and also to ideally mute any domestic dissent to the idea. The second reason is to set up recruiting posts for the PLA SSF. The centers provide a ready manpower pool for the Strategic Support Force and other units that the PLA may want to establish.

There are some drawbacks to Xi’s push for military-civilian fusion, and increased governmental control over the Internet, namely that the people will push back against it. So far, Beijing has gambled that the rewards are worth the risks. The recent unrest in Hong Kong may have encouraged an acceleration of MCF, as the regime worries the Internet could be used for greater popular mobilization against it. Currently, the protest movement has been stifled, no small part due to enforced quarantines during the coronavirus pandemic. However, with the implementation of the new national security law (香港国家安全維持法) for Hong Kong, and its draconian punishments, the situation may change rapidly for Beijing. (Xinhua, June 30, 2020) The law does not specify the utility of MCF in Hong Kong, but the semi-autonomous region might prove to be a test case for the regime’s integration plans. (For the law itself see: Xinhua, June 30, 2020)

MCF Integration after the Covid-19 Pandemic

Since the Covid-19 pandemic began, Beijing has sought to strengthen and expand MCF. (People’s Daily, May 13, 2020) This is, perhaps, the next stage in the development of the military-civilian integration plan that Xi and the CCP envision. (Cyberspace Administration of China, March 13, 2018) This acceleration of MCF has not gone without notice by the United States, and other foreign states. Beijing experienced significant criticism during the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly from the Trump administration, for its handling of the coronavirus situation to perceived meddling in the 2020 US presidential election. (Nikkei Asia, October 28, 2020) Part of this criticism focused on China’s military-civilian fusion to the point the United States has blacklisted several Chinese companies with strong links to the PLA. (The Diplomat, November 30, 2020)

China has pushed back on these criticisms, stating that the US, in its history, has commonly practiced MCF, and that China will take all necessary measures to protect its interests. (Beijing Daily, December 3, 2020) The criticism from the US and its allies has caused consternation from China, as Beijing continues to denounce the criticism. (Foreign Ministry of China, January 15, 2021) Despite this, or perhaps because of, the hostility Xi remains adamant that China will continue on its path of technological development, creating a new cybersecurity paradigm, which includes military-civilian fusion. (China Daily, November 24, 2020) It is a stance that Beijing is not backing away from, and appears unwilling to compromise on. (Cybersecurity Administration of China, March 15, 2021)

China plans to establish more innovation centers in the future, promote more reforms, and promote Xi’s vision of China as a technological superpower on the cutting edge of modernization. Many of these changes have seemingly benign intent, to improve the standard of living among everyday Chinese. However, beneath that veneer the party-state seeks to exert its total control over the cybersphere. This control, ideally for the CCP, will occur gradually over time, in order to avoid any dissent, either domestic or foreign, to its ultimate goals.

To that end, military-civilian integration on cyber initiatives will continue, and may accelerate yet again. Along with Xi, the PLA has pushed back against American assertions that military-civilian fusion is anything but benign. (People’s Daily, November 13, 2020) For China’s military, MCF serves as a conduit for fresh recruits to the Strategic Support Force and other units that conduct informatized warfare, where the PLA is increasingly convinced any conflict with the US will be conducted. China also worries about the Internet as a staging ground for anti-regime activism, and would prefer to have this unpredictable medium under more control.

Conclusion

Military-civilian fusion is not a new concept for China, nor did it start with Xi Jinping, however it is integral to the party-state’s strategy on making China a cyber superpower and ultimately centralizing control of cyberspace. This integration is not exclusive to the cybersphere, but it does play a key role in how Beijing wants to shape its cybersphere for the future.

If military-civilian fusion is to succeed for China, then it must be done through a compliant population, or at least an unsuspecting one. The expansion of cyber innovation centers throughout China serves the purpose of both mollifying the people and recruiting fresh talent into the PLA. However, Xi must walk a tightrope between two extremes in this approach. Move too quickly on military-civilian integration and it risks alienating the people, and foreign adversaries alike. Move too slowly and Beijing risks losing its moment to obtain more control over its cyberspace and create momentum toward cyber sovereignty.

Biography: James MacHaffie is an independent analyst on Asian security topics, including cybersecurity. He holds a doctorate in international politics from the University of Leicester.