By Sarosh Bana.

At their 2nd Virtual Summit on Monday, the Indian and Australian Prime Ministers, Narendra Modi and Scott Morrison, papered over the differences that had riven their online Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) summit with US President Joe Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on 3 March.

The Quad summit had been convened to discuss “the war against Ukraine and its implications for the Indo-Pacific”, but Modi’s refusal to side with his three partners in directly condemning Putin or endorsing the US-NATO drive against Russia had isolated India.

Under the circumstances, a positive tangible was the return to India, a day before the Modi-Morrison summit, of 29 priceless Indian antiquities that had surreptitiously ended up in Australian art galleries over the years.

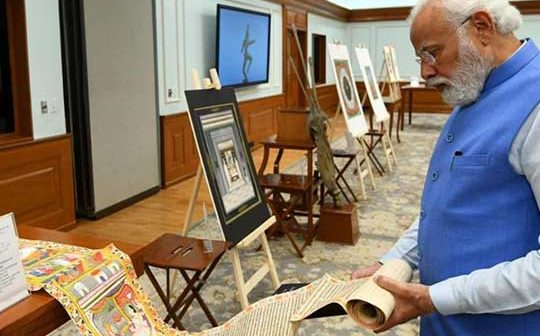

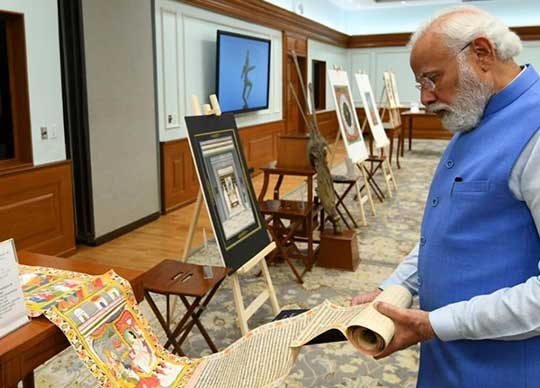

Modi appraised the repatriated artworks ahead of his virtual meeting with Morrison, and thanked Canberra for resolving an international art scandal, even as the two sides went through their expected paces in ‘reviewing’ their comprehensive strategic partnership.

The returned artefacts include Shiva Bhairava, a 9th or 10th century sandstone sculpture of a fierce manifestation of Lord Shiva, a 12th century bronze figurine of the child saint Sambandar, and a 19th century Kangra school painting of Shiva and his consort Parvati.

The artefacts, primarily sculptures and paintings, would be handed over to the temples from where they were stolen, some as long as half a century ago, said India’s Culture Minister G. Kishan Reddy. Many other such recovered treasures are housed in the Gallery of Retrieved and Confiscated Antiquities, as part of the Central Antiquity Collection at Purana Qila in New Delhi.

Canberra’s decision to return these exceptional works was prompted by New Delhi’s request for a service of process on grounds that they had been stolen and sold fraudulently to Australian authorities. Australia’s then Prime Minister Tony Abbott had returned two antique statues of Hindu deities during his state visit to India in 2014. These statues had been on display in Australian galleries, including the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra, after having been stolen from temples in Tamil Nadu. One sculpture was a 10th century Ardhanariswara, personifying Shiva in half-female form, while the other was of Nataraja, the dancing Shiva, belonging to the Chola dynasty of the 11th-12th century.

The NGA subsequently returned two more works of art to India in 2016, three in 2019 and 14 last year. Last October, US investigators also returned 248 ancient works valued at $15 million to India.

This plunder of heritage and its fraudulent sale have been the handiwork of Subhash Kapoor, a 73-year-old American citizen of Indian origin who ran the Art of the Past gallery at New York’s Madison Avenue. The bronze Nataraja, for instance, was purchased from him by the NGA in 2008 at a price of $5.1 million, while the Ardhanariswara stone statue was sold by him to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2004 for $280,374.

Kapoor was arrested in Germany in 2011 and subsequently extradited to India where he is incarcerated. He is being prosecuted on charges of larceny and trafficking in connection with more than 2,500 South Asian antiquities, many of which he pilfered from old village shrines. There is also a warrant for his arrest from the Manhattan district attorney’s office on similar charges, with Asian artefacts worth over $20 million having been seized from his Manhattan properties.

The NGA states it has been its Asian Art Provenance Project, launched in 2014, which has resulted in deaccession and repatriation of such works to their countries of origin. In doing so, the Gallery claims to have complied with the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, which urges States Parties to take measures to prohibit and prevent the illicit trafficking of cultural property.

The repatriation of the stolen Indian antiquities, however, raises a larger issue. And that is whether institutions like the NGA, which is a designated Australian Government Agency, can walk away from such episodes and be absolved of all responsibility, liability and criminality simply because they are returning stolen exhibits. For instance, would Kapoor walk free if he were to return the ill-gotten antiquities?

“If the allegations regarding Mr Kapoor are proven to be true, then our Gallery, along with leading museums around the world, will have been the victim of a most audacious act of fraud,” maintains the NGA. “If proven, this fraud has involved the elaborate falsification of documents by a long-established New York art dealer who had been dealing with leading international museums for almost 40 years.”

Lawyer and criminologist Duncan Chappell from the University of Sydney Law School had reportedly said that the NGA had probably not undertaken due diligence in a manner one would have expected of a major institution. Terming the gallery “naive” in the way it handled this matter, he felt its suspicions about the artworks’ antecedents should have been aroused, because obtaining any Indian antiquities was in itself “always a highly hazardous position” in view of the antiquities laws prevalent there. Kapoor had used his gallery website, since closed, to highlight the many prominent museums he used to professionally deal with, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery of Art, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, and the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California.

Illegal excavations and the illicit trade in cultural property have been flourishing just because this criminality, that desecrates a nation’s heritage and cultural wealth, is patronised, unwittingly or otherwise, by individual art collectors and national museums and galleries. Seeking to tighten its legislation of 2007 on the protection of cultural objects, the German government noted that although it is “common practice for museums not to purchase cultural objects of indeterminate provenance”, the fact remains that “illegally excavated or illicitly exported cultural treasures are still being bought and sold”.

India especially has an extraordinarily rich, vast and diverse cultural history in the form of built heritage, archaeological sites and ruins since prehistoric times. The sheer magnitude in numbers alone is overwhelming and these are the symbols of both cultural expression and evolution.

The country’s Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972 stipulates “imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months, but which may extend to three years and with fine” for anyone exporting or attempting to export any antiquity or art treasure. Antiquities and art treasures have been notified as objects that have been in existence for not less than 100 years. All archaeological objects and sites have moreover been granted state ownership.

UNESCO indicates, however, that even following the enactment of its Antiquities Act, India reported thefts of nearly 3,000 antiquities between 1977 and 1979, and within the next decade, more than 50,000 idols, icons, artefacts and antiquities were smuggled out of the country. The UN agency attributes this mass loot also to “institutional negligence, inadequate research, and poor conservation measures”. The establishment of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) during British rule in 1861 was intended to protect the cultural heritage of the nation, maintain ancient monuments, and research and monitor archaeological sites. Now attached to the Ministry of Culture, the ASI has the responsibility to protect and preserve 3,650 monuments from different periods, ranging from prehistoric times to the colonial period.

The lack of enforcement of the laws nevertheless remains a major concern. “There is no comprehensive record in the form of a database where such archaeological resources in terms of built heritage, sites and antiquities can be referred,” said Meena Gautam, then Director of the ASI’s National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities. “As a result, this finite, non-renewable and irreplaceable resource of our country is fast disappearing without any record for posterity.” She underscores “an urgent need” for a proper survey of such resources and, based on that, the formulation of an appropriate archaeological heritage resource management and policy. The National Mission estimates approximately seven million antiquities in India, but has hitherto managed to register only around 480,000 of them. Experts, however, believe the calculation of the antiquities is grossly underestimated.

The NGA, whose Asian art collection holds approximately 5,000 items, had said, “The NGA acknowledges that there are works in the collection whose provenance and legal status needs a renewed level of scrutiny.”

Indeed, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia had itself initiated an independent review to address provenance issues of its Asian art collection, provenance being the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of an historical object.