Columb Strack, principal Middle East analyst, IHS Markit

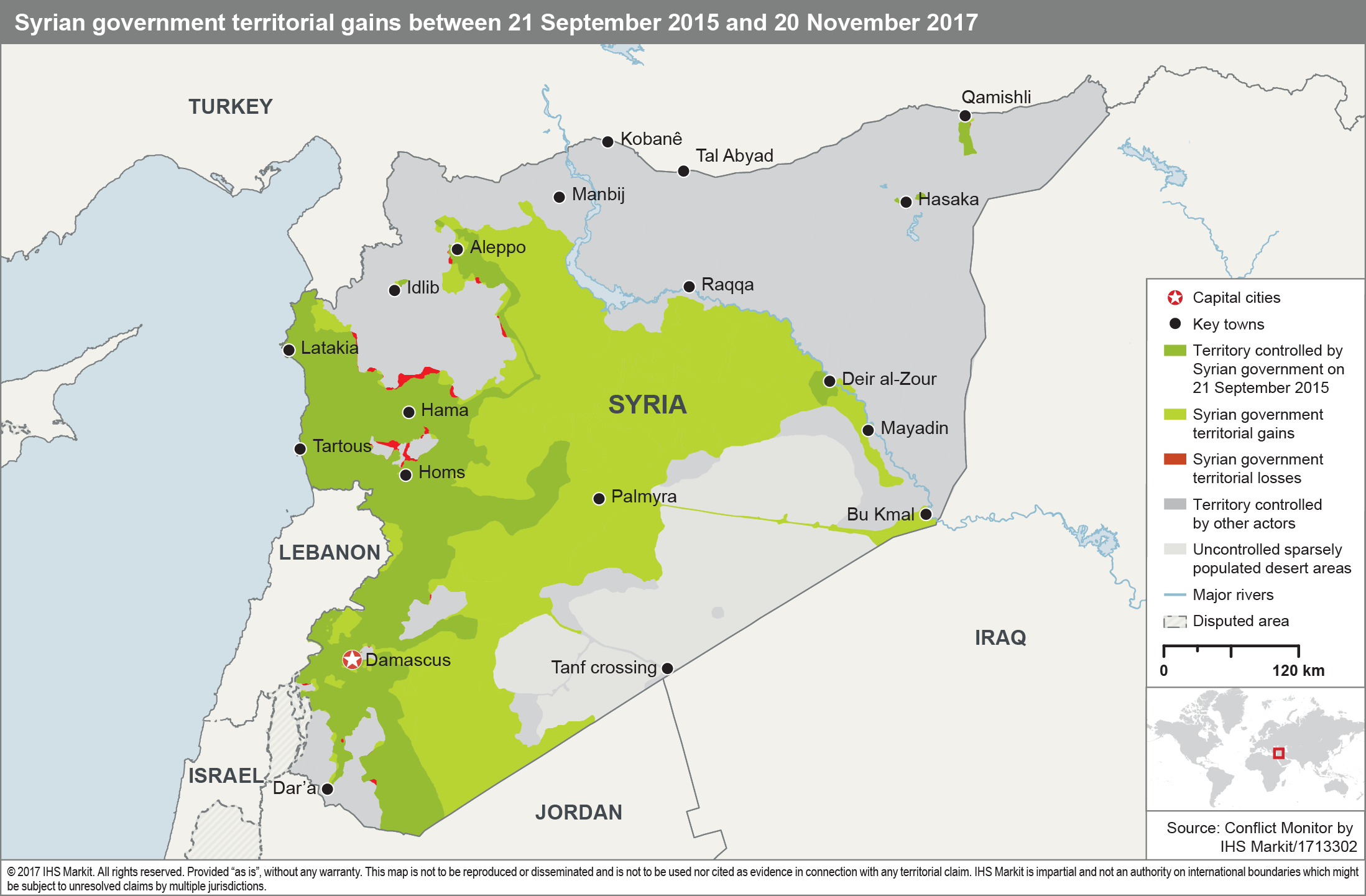

The Syrian army and its allies announced on 19 November that they had regained control of Bu Kmal, the last significant town held by the Islamic State in Syria.

The Syrian army and its allies announced on 19 November that they had regained control of Bu Kmal, the last significant town held by the Islamic State in Syria.

Outlook and implications:

- The Syrian government is unlikely to adhere to the Astana de-escalation zones agreement once it has fully re-established control over Deir al-Zour province.

- US-backed Kurdish components of the SDF are likely to hand control of Deir al-Zour’s oilfields back to the Syrian government, despite likely resistance from Sunni tribal factions.

- The Syrian Kurds are likely to be granted a degree of political autonomy within the Syrian Arab Republic, but an agreement will be contingent on the return of territory captured from the Islamic State by the SDF.

- Turkey is likely to be presented with a fait accompli on Kurdish autonomy, as approved by Russia, despite their objections.

- Israel is likely to seek to communicate and enforce its ‘Red Lines’ over the deployment of Iranian proxies near the Golan, risking escalation to another war with Hizbullah that would probably involve Syria.

The Islamic State is likely to lose what remains of its ‘caliphate’ by early 2018, reverting to a rural-based insurgency. However, once the government has re-established control over Deir al-Zour’s oil fields and population centres along the Euphrates, it will probably no longer adhere to the de-escalation zones plan in the west. President Bashar al-Assad has consistently stated that he intends to re-assert government control over all Syrian territory, and he likely calculates that he is now in a position to do so.

The government’s likely priorities in the coming months will be to establish control over the country’s main Damascus-Homs-Aleppo highway and to re-open the border crossings with Jordan and Iraq to trade. The remaining smaller pockets of insurgent control around Damascus and Homs are likely to be returned to government control over the coming year, either by negotiation or by force.

The future status of Deir al-Zour’s oil fields

The US-backed, predominantly Kurdish, Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) took control of the al-Omar and al-Tanak oil fields in Deir al-Zour province in October, amid unverified claims that they had negotiated a handover of the fields with Islamic State-affiliated tribesmen. If reports of Islamic State fighters defecting to the SDF are correct — which IHS Markit assesses are plausible — these were probably local tribal components of the Islamic State, rather than more ideologically committed foreign fighters. Faced with inevitable defeat, they preferred the oil fields to fall into the hands of the SDF, rather than the Syrian government.

The government will almost certainly prioritise recovery of the al-Omar and other fields from the SDF in the coming months. Russian efforts have accelerated since early October to co-ordinate between Damascus and Kurdish representatives, which reportedly resulted in the SDF handing over the Conoco gas facility in northern Deir al-Zour province to the Syrian army on 18 October. Failing a negotiated handover of the other fields, the government’s most likely course of action would be to announce that they are reclaiming them by force. We assess that US-backed Kurdish components of the SDF would withdraw from the fields in that event, probably as part of a wider agreement to initiate negotiations on autonomy for the Kurds. Sunni Arab tribal components of the SDF and defected Islamic State tribesmen would be more likely to resist the government militarily.

Demands for Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria

President Assad has made it clear that he will not accept the splitting of the Syrian state, and will demand that territory currently held by the SDF, including the city of Raqqa, reverts to government control. The Syrian government and the de facto Kurdish administration will most likely try to avoid military conflict over this territory. The Kurds have very little incentive to sacrifice more Kurdish lives for traditionally Sunni territory that they have no realistic expectation of permanently holding, and the Syrian government will not want to become engaged concurrently in fighting Syrian Kurds and the existing Sunni insurgency in western Syria. Our assessment is that the most likely outcome will be a negotiated handover of territory that the Kurds seized from the Islamic State back to the Syrian government, in return for some degree of Kurdish autonomy within the Syrian national state.

The Syrian government appears willing to grant the Kurds some autonomy within the existing state framework. In September, the state news agency SANA quoted Syria’s foreign minister, Walid al-Moualem, as saying that the government was open to negotiations with the Kurds over a deal for greater autonomy within the borders of the Syrian Arab Republic. The Kurdish Democratic Union Party’s (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat: PYD) official position is that Syria’s Kurds are looking for federalism, not partition of Syria. Negotiations are likely to be contingent on the SDF returning territory captured from the Islamic State since 2014.

Turkey’s deployment in support of Sunni opposition in Idlib

The rebel-held Idlib pocket is the most likely of the designated de-escalation zones in which there could be a significant intensification of fighting once the government has re-established control in Deir al-Zour. The government’s likely main objective in Idlib province will be to re-establish control over the strategically important M5 highway that links the country’s main cities of Damascus, Homs, and Aleppo. This would probably be possible without a direct military confrontation with Turkish forces deployed further to the west, and would leave Turkey to defend the interests of Syria’s Sunni opposition in an area adjacent to its border, which is of low strategic value to the government.

Turkey’s primary objective in Syria is to prevent the establishment of an autonomous Kurdish entity along its border with Syria. The deployment of Turkish troops to Idlib province in October, which is only likely to have happened with Russian agreement, is aimed at deterring the Syrian government from attempting to retake all of Idlib province. The Syrian government does not have the capability to expel the Turkish army from Idlib province militarily, and will probably be forced into negotiating a deal that will, at a minimum, involve an exclusion of the Afrin canton from Kurdish autonomy, and assurances that the policing of the border with Turkey will be returned from the YPG to government control. It is unlikely that Turkey will be able to prevent an agreement between Damascus and the Kurds, as approved by Russia, and they will probably be presented with a fait accompli, regardless of their objections.

Israel’s emerging ‘red lines’ in Syria

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated on 23 October that preventing Iran from establishing itself militarily in Syria was now Israel’s top strategic priority. Israel is concerned about Iran’s freedom of action to deploy at will not just proxies, but Iranian combat forces, across Syria. There is now a potential front line with Iran on Israel’s borders, and the strategic depth Israel has hitherto enjoyed from its geography has been eroded by the Iranian-supplied missiles available to Iran’s proxies in Syria. For Israel, the expansion of Iran’s influence increases the capability of its enemies to develop high-precision missiles and other advanced weapons in concealed/hardened sites in Syria and south Lebanon, reducing their dependence on land resupply, and the vulnerability of their supply line to interdiction by Israeli air strikes.

The net result of Iranian expansion increases the risk of a local confrontation with Israel in south Lebanon or the Golan escalating into a war, not just involving proxies but Syrian government, and potentially Iranian, forces. Israel has signalled its displeasure with US and Russian plans to allow the Syrian civil war to end with Iran having substantially expanded its military presence in the country, and is seeking to communicate its new ‘red lines’ in Syria. These appear to include a rejection of the presence of any hostile foreign forces west of the Damascus-Dar’a road, approximately 50 km from the Israeli-occupied Golan. Although Hizbullah is likely to respond to Israeli military action in an equivalent manner, Hizbullah will not be the only player, or the only Israeli target, involved and any response carries a risk of unintended escalation.